British Insulated and Helsby Few collectors will have heard of this

British company, but they were involved in telephones and cable manufacture from

the earliest days, and they played a big part in the development of the Australian

cable industry.

In 1884 J and G Crosland Taylor founded the Telegraph

Manufacturing Company in Helsby in England. They made batteries, insulated wire

and telegraph equipment. Within four years their lack of business experience was

showing, and an inept manager was driving them into trouble. A new manager and

a diversification into golf balls (made from gutta-percha, as used in their insulated

wire) got the company out of trouble, but they found it hard to attract skilled

staff to the quiet town of Helsby. In 1892 they moved much of the plant to a factory

in Liverpool. Further diversification followed. They produced a range of products

including bike tyres, and gained a large contract with the National Telephone

Company for telephone wire and 26-pair cable. This established them in the cable

market.

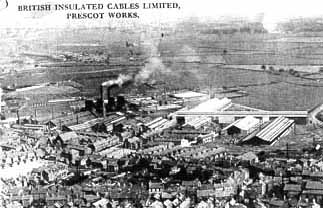

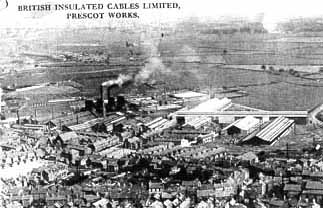

In 1902 they amalgamated with the British Insulated Wire Company of Prescot, in

Lancashire. British Insulated started in 1890 and had built up a good market for

insulated telephone, telegraph and electrical wiring. In 1899 they provided a

submarine cable to run under Sydney Harbour. The amalgamation was a good move

for both companies. British Insulated had the British and colonial patents for

the new paper-insulated dry core cables and a large factory in Prescot to make

it. TMC had a good range of telephone technology, which was a fast growing area,

and many contracts for telephone cable. The new company became British Insulated

and Helsby Cables Ltd .

In 1902 they amalgamated with the British Insulated Wire Company of Prescot, in

Lancashire. British Insulated started in 1890 and had built up a good market for

insulated telephone, telegraph and electrical wiring. In 1899 they provided a

submarine cable to run under Sydney Harbour. The amalgamation was a good move

for both companies. British Insulated had the British and colonial patents for

the new paper-insulated dry core cables and a large factory in Prescot to make

it. TMC had a good range of telephone technology, which was a fast growing area,

and many contracts for telephone cable. The new company became British Insulated

and Helsby Cables Ltd .

In 1903 BI&H built a new factory in Edge Lane, an outer suburb of Liverpool.

The factory was badly needed, as the existing factories could not keep up

with the demand. Business was growing rapidly and telephone exchange equipment

was being exported to, among other cities, Fremantle in Western Australia.

The two phones listed in the Australian Post Office 1914 manual were possibly

from this installation. They also exported large amounts of wire and insulators

to the developing Australian railways. They seem to be well-known in Western

Australia particularly.

BI&H was now building CB telephone

exchanges as well as phones. Their CB switchboards were quite successful, and

they equipped some large British cities with trunk exchanges for the British Post

Office. The design followed Western Electric practice but was based on a version

invented by J S Stone in the United States that had proved popular with the independent

telephone companies (and avoided the Western Electric patents). BI&H was now building CB telephone

exchanges as well as phones. Their CB switchboards were quite successful, and

they equipped some large British cities with trunk exchanges for the British Post

Office. The design followed Western Electric practice but was based on a version

invented by J S Stone in the United States that had proved popular with the independent

telephone companies (and avoided the Western Electric patents).

Although

information on BI&H phones is scarce and ambiguous, some trends are emerging

as collectors forward information. Rather than build their own phones completely,

they seem to have bought in Western Electric phones and parts initially. A typical

early phone will be standard Western Electric, but will carry at least one branded

BI&H part as well as BIH circuit diagrams inside the case and bellbox. They

started producing their own designs before the First World War, following the

move to Edge Lane. The production dates of the WE phones are well known, so this

gives us approximate dates for the BIH models.

Poole (1912) lists three examples of their CB phones. Some of these appear

to use unbranded Ericsson transmitters fitted to an unusual “radial arm”

whose purpose was “to accommodate to the different heights of the

persons using it”. This could have been a useful feature in the days

when the transmitters were less sensitive, but other companies managed to

do without it The desk set has an extendable handset shaft “so as

to accommodate the face length of any individual”. These phones are

pictured on the next page.

Jim Bateman’s book “History

of the Telephone in New South Wales” shows another and probably earlier design.

It is a three box wall phone similar to a Western Electric pattern but fitted

with an Ericsson receiver and a Manchester Shot transmitter in place of the usual

Blake transmitter.

The Australian

Post Office listed two BI&H phones in a 1914 technician’s

manual. One was a magneto wall phone with dual receivers. This is probably

the twin box model shown on the next page. These phones date from about 1886

to the early 1890s when the Solid Back transmitter was introduced. The other,

from the circuit diagram shown in the manual, was a CB candlestick style (see

next page). The circuit diagram shows provision for a second receiver. The

phone appears to be a rebadged Ericsson model. The picture is from Bob Freshwater’s

website (see Bibliography at the end of this chapter). Previous BIH candlestick

phones were WE-based, but I am not aware of any WE candlesticks being fitted

with a second receiver. In spite of this, the only candlestick known in Australia

(so far) is a WE model, so maybe the APO manual has the incorrect circuit

diagram from the later Ericsson model. By 1914 the APO had replaced many phones

inherited from the old state telephone administrations, so the BI&H phones

must have been reliable for the APO to retain them. In spite of this, they

appear to be almost unknown to collectors. The APO also listed BI&H switchboards.

By 1914 BI&H was building CB wallphones to the now standard BPO pattern

and these were listed in the APO’s 1914 handbook as Telephone No. 17. Although

BIH's catalogue picture shows an Ericsson transmitter, it would more likely have

been fitted with a Solid Back transmitter by this time, as per British Post Office

practice. A similar magneto model was also made. Other companies made the same

phone and only the numbers stamped into the back woodwork would identify it as

a BI&H.

The next page shows BI&H’s “Pantophone”.

This was a phonopore-type telephone for use on railway telegraph lines. Note that

they used an Ericsson transmitter for the "ring" signal. Like most other

companies they also produced a small range of intercom phones.

At the

White City Exposition in 1908 one of the new American automatic telephone exchanges

was demonstrated, probably by Strowger’s company Automatic Electric. It was

a refined operation, rather than the clumsy early versions. The phones used the

familiar ten-digit dial instead of the early “Knuckleduster” eleven-hole

dial. The exchanges ran reliably on a two-wire subscriber circuit, which provided

automatic ringing and busy tone. The new manager of BI&H, Mr Dane Sinclair,

could see that this was the way of the future. He had actually patented an automatic

switchboard in Britain in 1883 and he was well-placed to judge the efficiency of

the Strowger design. He had been Engineer-in-Chief of the National Telephone Company,

giving him experience of the competing Gilliland, Betulander and Lorimer systems

and he knew their deficiencies. He urged the company to get the British rights

to the Strowger system.

The Board agreed, and set up a new company to build the equipment – the

Automatic Telephone Manufacturing Company. They acquired the rights in 1911.

Although they were supposed to be a separate company to BI&H, the Post

Office allocated them the manufacturer code of “H” (for Helsby”).

The old company, BI&H, now concentrated on cables. The first British-built

Automatic Telephone Manufacturing exchange was assembled from imported parts

and installed at Epsom, and the company took over the Edge Lane factory from

its parent. They began making their own equipment in 1912. This gave ATM a

head start on other potential manufacturers like Ericsson and Western Electric.

ATM began producing modified and reengineered versions of the Strowger equipment

and was soon building a strongly British product. This was exported to Britain’s

colonial markets as well. It also marked the end of BI&H as CB telephone

manufacturers. The British Post Office had decided on a small range of standardized

phones to their own designs and the BI&H phones were dropped. BI&H

briefly produced a CB wall phone for the BPO, but it soon became evident that

there was no point in them producing anything but automatic phones. The original

company became British Insulated Cables in 1925 to reflect their new emphasis.

During World War 1 the Australian Government found that they had no

local manufacturer of electrical wire, a vital military supply. They arranged

a joint manufacturing deal between BI&H and local investors. The new Australian

company was called Metal Manufactures Limited. Their factory was at Port Kembla,

south of Sydney, where they produced copper rod for drawing into wire. By 1923

they were producing 3000 tonnes of copper rod per year, and they were diversifying

into copper tube as well. They absorbed another local company, Austral Bronze

Co. Ltd., who produced rolled brass and copper sheet.

During World War

2 the strategic value of these companies was realised by the Government, but it

turned out that Australia still did not have a local manufacturer of insulated

cables. A new consortium of Metal Manufactures, Olympic Tyres, and, once again,

British Insulated was formed. It was called Cablemakers Australia Pty Ltd. Following

another amalgamation in 1945 British Insulated became British Insulated &

Callenders Cables, and was for a time the world’s biggest cable manufacturer.

BI&C eventually became part of the Marconi group of British companies,

and it is interesting to note that Marconi appropriated the company’s previous

history as its own. On its website under the heading “Marconi Celebrates

a Century of Switching Innovation in Liverpool”, (December 4 2003), they

modestly claimed “Known as British Insulated and Helsby Cables, Marconi began

manufacturing manual telephone exchanges in Liverpool in December 1903. “

To the victor goes the right to rewrite history, but Marconi fell in its turn

too. See the chapter on the General Electric Company for details.

The

original TMC factory in Helsby was finally closed in 2002.

Bibliography

This article is based on a detailed history of the company published in 1989

by Andrew Emmerson and available at http://strowger-net.telefoonmuseum.com/.

Further information is from

Poole J “The Practical Telephone Handbook” London 1904

Commonwealth of Australia Technicians Handbook “Connections of Telephonic

Apparatus and Circuits” 1914

Bateman J “The History of the Telephone in New South Wales”

1980

Liverpool National Museum’s Archives Dept.. Information Sheet 63,

Marconi

Celebrates a Century of Switching Innovation in Liverpool

University of Melbourne – “Technology in Australia 1788-1988”

Sigtel “The

Girl-less, Cuss-less Telephone” Website article

and information

and photos kindly supplied by Ric Havyatt and Brian O"Donnell.  Typical B.I. & H. Telephones

Typical B.I. & H. Telephones

If you have reached this page through a Search Engine, this will take you to the front page of the website If you have reached this page through a Search Engine, this will take you to the front page of the website

|

In 1902 they amalgamated with the British Insulated Wire Company of Prescot, in

Lancashire. British Insulated started in 1890 and had built up a good market for

insulated telephone, telegraph and electrical wiring. In 1899 they provided a

submarine cable to run under Sydney Harbour. The amalgamation was a good move

for both companies. British Insulated had the British and colonial patents for

the new paper-insulated dry core cables and a large factory in Prescot to make

it. TMC had a good range of telephone technology, which was a fast growing area,

and many contracts for telephone cable. The new company became British Insulated

and Helsby Cables Ltd .

In 1902 they amalgamated with the British Insulated Wire Company of Prescot, in

Lancashire. British Insulated started in 1890 and had built up a good market for

insulated telephone, telegraph and electrical wiring. In 1899 they provided a

submarine cable to run under Sydney Harbour. The amalgamation was a good move

for both companies. British Insulated had the British and colonial patents for

the new paper-insulated dry core cables and a large factory in Prescot to make

it. TMC had a good range of telephone technology, which was a fast growing area,

and many contracts for telephone cable. The new company became British Insulated

and Helsby Cables Ltd .  BI&H was now building CB telephone

exchanges as well as phones. Their CB switchboards were quite successful, and

they equipped some large British cities with trunk exchanges for the British Post

Office. The design followed Western Electric practice but was based on a version

invented by J S Stone in the United States that had proved popular with the independent

telephone companies (and avoided the Western Electric patents).

BI&H was now building CB telephone

exchanges as well as phones. Their CB switchboards were quite successful, and

they equipped some large British cities with trunk exchanges for the British Post

Office. The design followed Western Electric practice but was based on a version

invented by J S Stone in the United States that had proved popular with the independent

telephone companies (and avoided the Western Electric patents).